Nancy's Musings

March 12, 2013

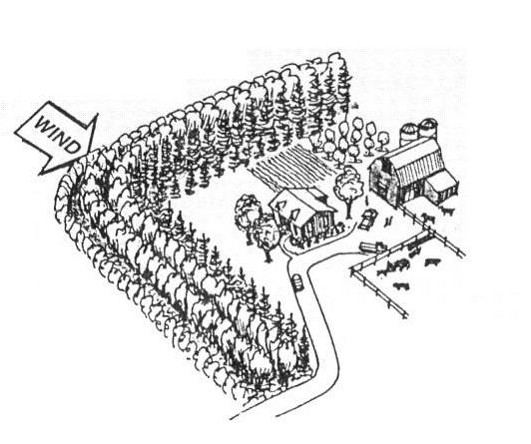

In my historical fiction book series, Earth’s Memories, Deborah Nelson’s county agent advises her to do several things to control the effects of the soil-blowing winds on her northwest Kansas farm. When he advocates that she plant shelterbelts, the concept is so new to her that she has to ask for an explanation. She and her cooperative friends immediately prepare for the arrival of the Civilian Conservation Corps that will plant row upon row of trees in specified areas on her farm and their ranches.

Preparation involves working the soil, building rabbit guards, and providing mulch. When the Corps finishes with the trees, Deborah’s backbreaking work really begins: watering the trees regularly against the continuing drought of the 1930s.

Records were kept. More than 200 million trees and shrubs were planted to windbreaks on 30,000 farms throughout the Great Plains between 1935 and 1942 according to the Kansas Forest Service today.

The second chapter of article 20 of Kansas state statutes indicate “soil erosion caused by wind or dust storms is declared to be destructive to the natural resources of the state and a menace to the health and well-being of our citizens.” The statutes go on to say it is “the duty of Kansas landowners to conserve the natural resources of the state, and to prevent the injurious effects of dust storms by planting perennial grasses, shrubs, and trees.”

Some of Deborah Nelson’s skeptical neighbors in my books thought shelterbelts and terraces just took away crop space, and wouldn’t consider them. Today more than 30 years of research at Nebraska University show that shelterbelts increase wheat yields by 15 percent, corn by 12 percent, and soybeans by 17.

Now here is the sad news. Many of the 1930s windbreaks have been removed and are continuing to be removed today to make way for pivot irrigation systems and to make way for more farm ground due to high prices for crops.

We don’t see very many field shelterbelts today, but there is no doubt about the drought in Kansas. 76% of our state is in extreme drought and the rest has exceptional drought. Despite the varying amounts of snow the state has had recently, predictions are that dust storms and soil erosion will continue into spring of 2013.

KSU soil scientists estimate 2 tons per acre per year of topsoil are being lost to wind erosion on cultivated cropland in Kansas.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

February 26, 2013

John drives me to town several times a week for therapy, and I pay close attention to the effects of the drought here in northwest Kansas. This past summer and fall I watched a herd of cattle being moved regularly from one pasture to the next.

Then an electric fence was put up and the herd grazed on land set aside for the temporary Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program. In the meantime, the last cutting of alfalfa was finished, and eventually the herd was moved onto that ground. From there they went to another pasture. It seems the rancher is carefully utilizing all of his land during this drought—and is fortunate to have big bails of alfalfa stacked near his feeding grounds for winter.

After the grazing on the alfalfa, the rancher irrigated it thoroughly; however, the grasslands haven’t fared so well—some few inches of snow only.

During the fall, farmers in the area harvested their corn, which they hauled to the elevator, and some was made into ensilage. Other dryland corn that didn’t produce was plowed into the ground.

Wheat was planted, and I waited with concern. Why? This is dryland wheat—and we have gotten little to no rain or snow. Some of the wheat came up … sparsely. Some came up very late. Some has yet to come up.

This week, our area of the state joined the rest of Kansas recently, joyfully anticipating snow. Six, eight, maybe nine inches fell that will melt down to very little moisture in an area that is many inches behind already.

We are thankful.

|